“Here I Dreamed”

More than half of Puerto Rico’s public schools have closed their doors in the last 10 years. Government officials justified the “consolidations,” saying hurricane damage and declining student enrollment necessitated them. In the years since, some schools have found new life as community centers, while others have been leased or sold. The majority of buildings, however, decompose like rotting corpses, their bones swaddled in nature’s eerie embrace, remnants of past lives slowly disintegrating into earth.

Photographed in March 2023 as part of UNC Global Story. See more from the project at www.isladefuerza.unc.edu

Inside Escuela Intermedia Marcelino Canino Canino in Dorado, which closed in 2018, the sign “Bienvenidos”, or “Welcome”, is still displayed in a former technology classroom. Stepping into an abandoned school can feel like entering another time. Desks rot in permanent rows. Ants creep along the spines of old textbooks. White chalk, scrawled on blackboards and never erased, marks the last day of school.

At Escuela Jose de Diego in Vega Baja, mold proliferates on the surfaces of desks and chairs. Amid haunting silence, life still abounds. Trees stretch their limbs through old windows while flowers blossom in the crevices of crumbling school walls. Crabs make their homes in bathroom sinks and iguanas rest on cold cement floors. Nature has begun to reclaim the classrooms in the years since the school’s closure in 2016.

A biography of Antonio Rafael Barceló, a prominent 20th century politician and lawyer, lies abandoned on a desk at Escuela Jose de Diego in Vega Baja. Barceló’s life motto, “Puerto Rico por encima de todo” (“Puerto Rico above all else”) is reflected in his work to establish educational spaces like The School of Tropical Medicine. The school was later incorporated as part of The University of Puerto Rico, the island’s oldest University. The education crisis extends beyond primary and secondary schools; UPR has lost nearly half its budget since 2017.

Tree branches wrap around former school buildings at Escuela Intermedia Marcelino Canino Canino in Dorado. The majority of closures (65%) occurred in rural areas, where distance between schools is greater and disruptions in children’s transportation to and from class placed greater burdens on caregivers to navigate changes.

The body of a horse is preserved in a bed of feces like an archeological relic at Escuela Elemental Alfonso Lopez Garcia in Dorado. In the time since their initial closure, some schools have been revived for other purposes like stables, only to further decay.

A gate is left open at Escuela Rosa M. Rodriguez in Vega Baja, where neighbors upkeep the school yard and utilize the space for community classes. In the absence of government action, some neighborhoods have taken it upon themselves to maintain the school grounds.

A billboard in a hallway at Escuela Elemental Alfonso Lopez Garcia in Dorado reads, “Good Work”. Julia Keleher, Philadelphia native appointed Puerto Rico Secretary of Education in 2016, was the architect behind many of the school closures. In 2019, she resigned from her role. “I regret the pain that [closures] caused communities,” Keleher said at a press conference in 2019 following her announcement that she would be stepping down. “But somebody had to be the responsible adult in the room.” Keleher was arrested and imprisoned in 2021 on account of conspiracy to commit fraud during her time as secretary.

An empty court at Escuela Marcelino Canino Canino in Dorado was once filled with children bouncing basketballs and batting ping pong balls back and forth in friendly competition. Now, the space is quiet. School spaces represent more than learning how to multiply numbers and write essays: they are places of cohesion and connection.

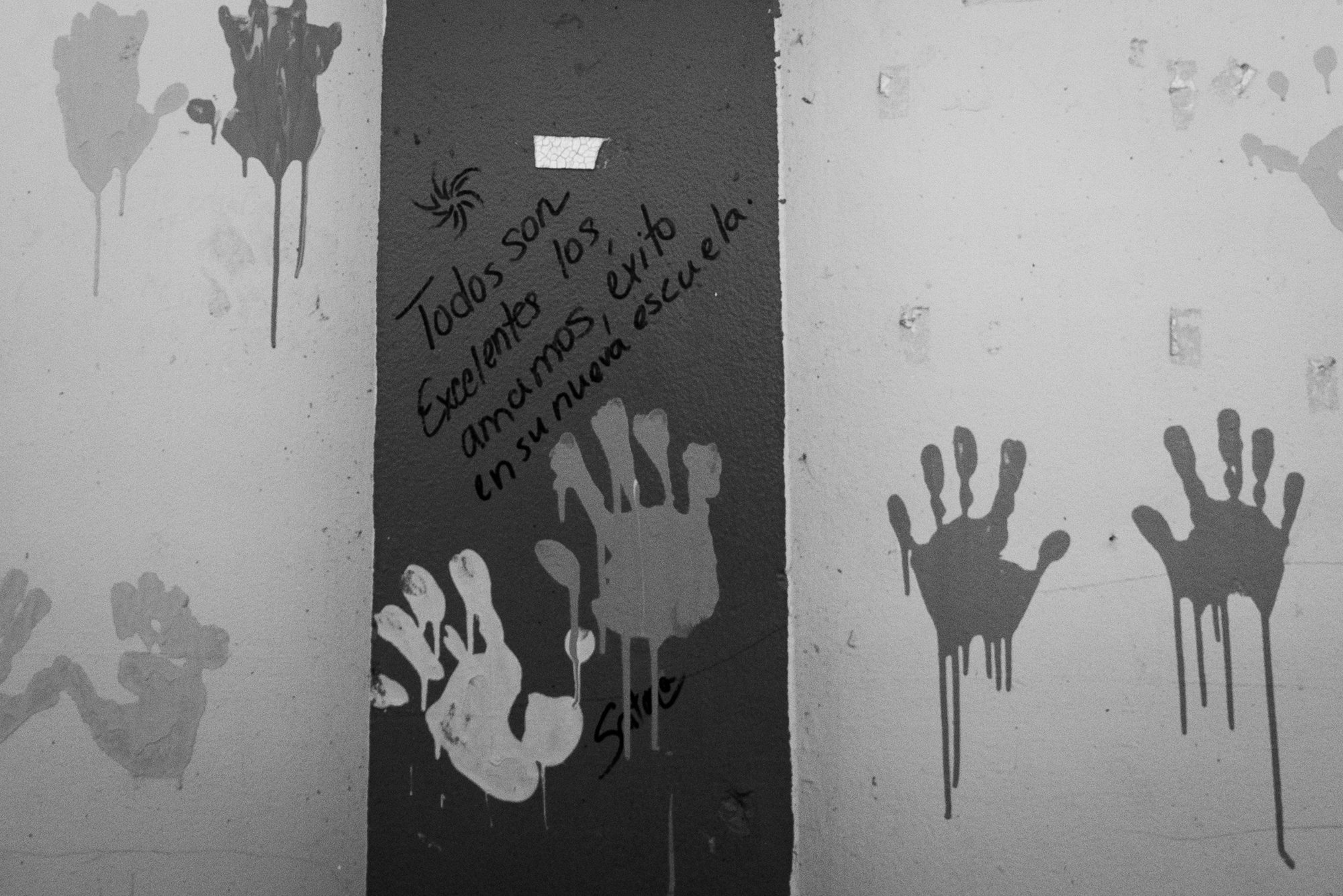

“You all are excellent, we love you and wish you success in your new school,” reads a message in a hallway at Escuela Elemental Alfonso Lopez Garcia in Dorado. Teachers left notes for their former pupils on whiteboards, in hallways and online in Facebook pages. School closures fractured bonds between teachers and students.

Horses roam free through classrooms of the old Escuela Intermedia Marcelino Canino Canino in Dorado. To this day, some schools continue to be repurposed by community members for uses such as stables. New life is still being cultivated, even amidst the decay.

The remains of a rabbit’s legs spoil beneath a pile of textbooks at Escuela Jose de Diego in Vega Baja. Where students once read children’s books about animals, textbooks now serve as the final resting place of the island's living creatures.

“Here, I dreamed,” reads graffiti scrawled on the wall of a roofless classroom at Escuela Jose de Diego in Vega Baja — a reminder of what could have been. In spaces where children once imagined their futures and teachers built homes of learning, old visions are now laid to rest. Just as Puerto Rico is changing, so too are these empty buildings, the deaths of their past lives as schools creating space for new beginnings.